Curves and light

On the magic of Barbara Hepworth

Corinthos by Barbara Hepworth has the shine and curve of a conker that’s just come out of its shell –a gorgeous, deep mahogany on the outside and on the inside a bright, clean white. That contrast is bracing and exhilarating and when I first saw this sculpture it affected me quite viscerally: I had a strange and powerful urge to place my mouth against it and lick. It’s quite an object: Hepworth carved it out of a huge piece of guarea hardwood which was gifted to her by a friend and started work on it in 1954 after returning from holiday in Greece. Her son Paul had recently been killed in a plane crash; in the few biographical accounts I’ve read of this time, the sculpture’s creation is placed in relation to this tragic loss and there is definitely something tender about the piece (though there were more obvious/ literal tributes to Paul in later work).

I didn’t know any of this background when I first came across Corinthos in 2011. My then boyfriend and I were visiting Liverpool for the weekend and we’d gone our separate ways for a few hours. I was having a deeply nourishing solo wander through the Tate and there it stood in my path, solid and arresting against the bright pink gallery walls. I was captivated. Is this a common or obvious response to Hepworth? I’m not a Visual Arts Guy as such, so I still don’t really know - at this point I’d never heard of her and this was the first sculpture of hers I’d ever knowingly seen (though obviously I now know what a huge and significant figure she was in the art world). After this I became a proper fan, though, and Hepworth’s work has gradually acquired something close to talismanic status in my life.

Last week I made a pilgrimage to her studio and sculpture garden in St Ives. This was a trip I’d originally planned as a reward for finishing my PhD in 2020 and which was put off for several years due to the pandemic/ being skint/ general life upheavals. While looking around those spaces last week, delighted to have finally made it (I visited twice in two days) I realised how little I’d actually known of Hepworth’s life up to that point, beyond some basic details about her marriage to painter Ben Nicholson and of course her major role in Modernist sculpture and art, and thought how nice it’s been to access my love for an artist unencumbered by hype or theory or biographical detail. As it is, I’ve created something of my own story out of her work and since that 2011 encounter there have been others – similarly spontaneous and unexpected – at what seemed like perfect moments: in 2015, in the grounds of Kenwood House, for example, where I went for a few consoling walks from my Archway flat in the days after my nan died in April and where, framed by blowsy, pink magnolia blossom, I came across the granite sculpture Monolith (Empyrean).

In 2019 I wrote a very raw essay about the aftermath of a painful breakup. The piece, which was published in Ulster University’s literary journal The Paperclip, was largely concerned with how completely unravelled I was by heartbreak, how beaten up and hollowed out I felt by the shock of it as I tried to move through the world (I feel like I’ve been hit by a car was, I remember, the most meaningful way I could describe how I was feeling most of the time) It ends with another chance run-in with a Hepworth sculpture, Curved Form (Delphi ) this time in the Ulster Museum in Belfast, which instantly soothed me. I see now that many of my observations in the essay were perhaps not terribly original but I’d been keen to try to put into words not only the sense of my profound physical weakening by grief but also how viscerally consoling Hepworth’s work was, in that space, at that time. The sculpture’s combination of solidity and fluidity took me, briefly, out of my enfeebled state - the smooth, conker-coloured wood again (it was carved from the same piece of guarea wood as Corinthos) the curves, the strings stretched taut across the space, all of it creating an ever-changing light and shadow and perspective: I wanted to throw my arms around it and place my cheek against the surface. A year after that breakup I went to Orkney with some friends – a trip arranged deliberately as a distraction from the milestone – and on our last day, we sheltered from the rain in the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness. Here there were several of Hepworth’s pieces, collected by her friend author and peace activist Margaret Gardiner (the same friend who had given her the wood) Barbara was following me!

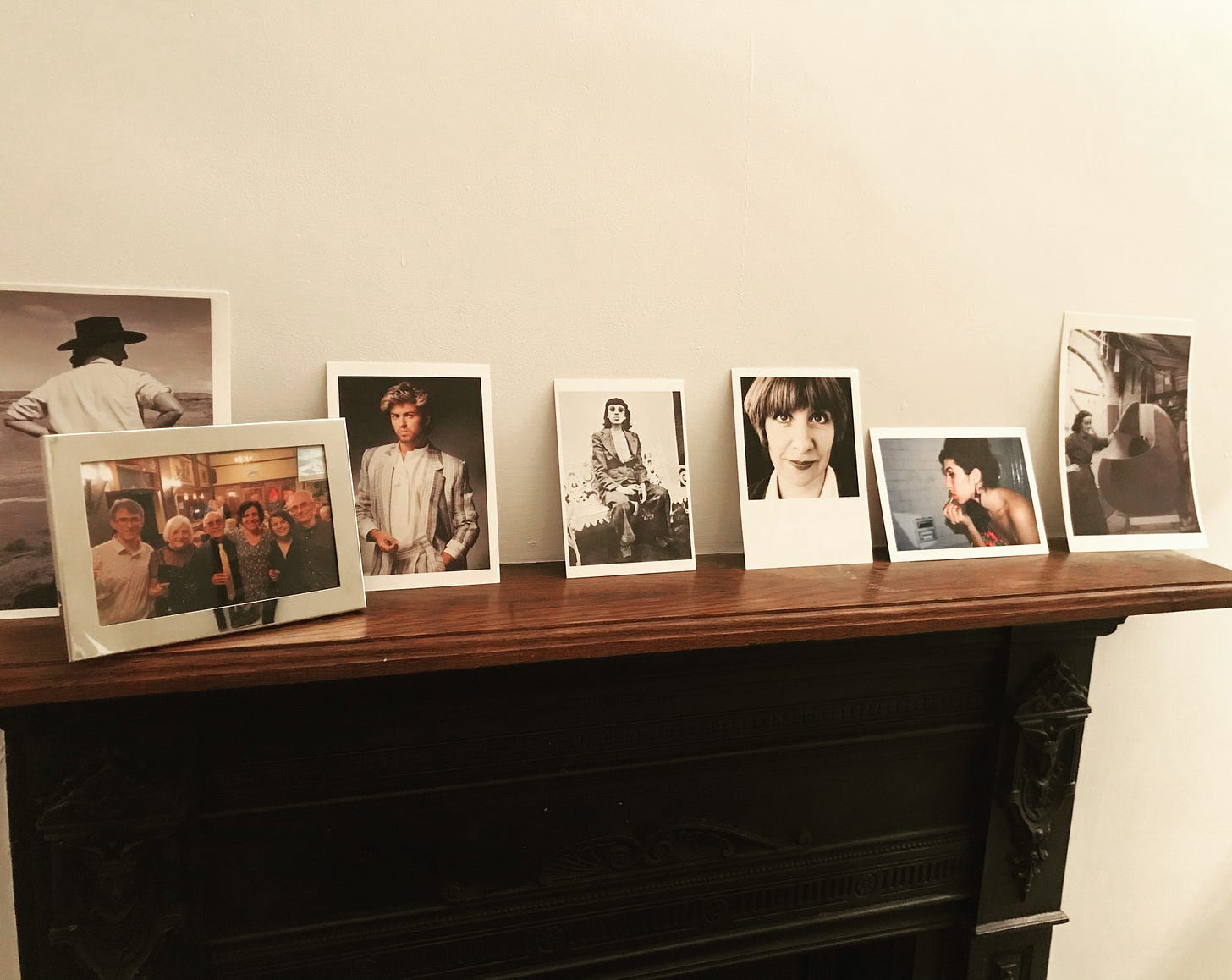

In 2015 the Tate Britain had a big showcase exhibition of Hepworth’s work and one of the postcards I bought from it was a photograph of her standing in her studio with a hand against the big imposing form of Corinthos. I pinned it above my desk in my London flat, a kind of inspirational, galvanising image of the woman artist alone and at work and that postcard travelled around with me in the following years as I rebuilt my life in Belfast among new people and new places. I lived in three different houses in the city and in all of them the placing of that picture on a bookshelf or a mantelpiece - next to postcards of Amy Winehouse, Georgia O’Keefe, Victoria Wood and George Michael, quite the line-up - was a key moment in the making of those homes, no matter how cold and inhospitable the space was otherwise. Here, Hepworth represents a woman making her own way, determined, creative and self-contained and I suppose when I looked at it, that’s how I wanted to see myself or at the very least what I wanted to strive towards.

I had a gorgeous time in St Ives last week but I was, most of the time, very conscious of my solitude. I was surrounded by couples and families squeezing the last out of the summer; in the restaurants and pubs there didn’t appear to be any other people on their own and there were a few moments when I sensed I was seen as a conspicuous oddity (I think in one restaurant a man turned to his girlfriend and actually pointed at me?!) I’m pretty hardened to this nonsense nowadays – I honestly don’t care what people think if I’m eating dinner on my own – but it doesn’t always make for comfortable times. In any case, the primary purpose of this particular holiday was not pubs or eating out, it was to look at art alongside some walking and appreciation of the landscape. So it was obviously a huge relief that in those settings – in the Tate, or Hepworth’s garden, or on a clifftop looking at the bright blue of the sea - I felt free of that watchfulness, that judgement and that there was something in the beauty there that actually made me feel sort of held.

I’ve been reading the 2002 novel Unless by Carol Shields over the past week and while away in Cornwall I noted down a striking, devastating sentence from it:

Bookish people, who are often maladroit people, persist in thinking they can master any subtlety as long as it’s been shaped into acceptable, expository prose.

I saw myself in that sentence, a bookish person forever trying to put things into clever, nice-sounding words - and there was something about St Ives in all its splendour, with its azure waters and its famously exquisite light, that made this line seem especially powerful (and yes, I’m aware of the irony of me describing this here in prose) It also made me think of Eliza Dolittle in My Fair Lady when she sings in exasperation to her suitor Freddy Words words words!/ I’m so sick of words! and wonders Is that all you blighters can do? On my second evening in St Ives I sat by the sea wall as my brain rattled with the restless internal monologue of the solo traveller, about where to eat dinner later and whether to apply more spf, where was the nearest toilet and maybe I should get my book out or try and write some thoughts down in my notebook. These moments can be exhausting when there’s no other presence there to help you smooth them down and I usually know now how to talk myself down from them. But this time I remembered that line from Shields’ novel: no words, I thought to myself, leaving my book in my bag, looking out at the water, leaning my head against the sun-warmed concrete, thinking of the shapes and reflections and shadows in Hepworth’s garden earlier. Give into sensation and beauty.